It is 2014, the year that the No Child Left Behind Act predicted as the year when all students in every state would be proficient in every subject. Unfortunately, we still have a long way to go. While the supporters of our modern age of standardized education accountability praise its efforts to close the achievement gap between white students and students of color, its critics claim that it has failed to live up to its promises and may even exacerbate inequality. As schooling has turned into a status competition, this test-driven approach to education provokes a number of unintended negative consequences for the students that the law is most intended to help. In some cases, it creates a strong incentive for schools to push out the lowest achieving students to create the appearance of improved test scores and to mask educational deficiencies [1]. Many scholars and advocacy groups have analyzed this “push-out” trend that is common in schools with inadequate resources, and identify a neglected public school system that is pressured by improvement criteria as the entry to the school-to-prison pipeline.

These accountability measures disproportionately burden urban schools, which are the most likely to serve students of color and students living in poverty [2]. In order to avoid government sanctions and intervention, these schools that depend on federal funding have a financial motivation to exclude the lowest-achieving students through a zero-tolerance approach to discipline during testing periods. There is a link between inadequate school financing and high rates of discipline – data show that poorly financed districts have lower graduation rates and higher suspension rates than wealthier districts. While pushing these students out of school and onto the streets may boost the school’s average test scores, it increases the student’s likelihood of partaking in delinquent behavior and placing them on the school-to-prison track.

According to Madeleine Cousineau’s submission as part of the Suspension Stories Project, there are three ways that schools raise their test scores through this loophole: 1. To hold back underachieving students from the grades in which tests will be administered, 2. to increase suspensions of low-achieving students during testing periods, or 3. to pressure low-achieving students to leave school or expel them, even if they have not violated any rule of school conduct. We are allowing a dangerously high percentage of students to disappear from the educational pipeline and putting them on the road to prison.

In David Figlio’s study of Florida school districts during the years surrounding the introduction of this high-stakes testing system, he found that during the testing window the mean suspension duration was higher for low-achieving students than high-achieving students, and was higher for black students than white students. In Flint City, Michigan, many schools suspended more than half of their Black and Latino students in a given year, and these rates also increased during testing periods. This selective discipline keeps low-performing students at home, missing the exam. NCLB then rewards these schools who effectively alter their student bodies.

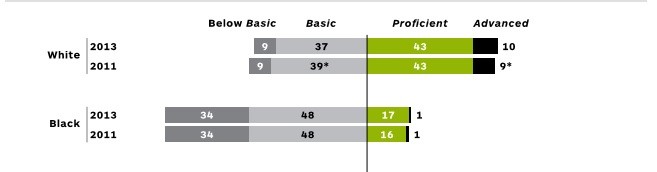

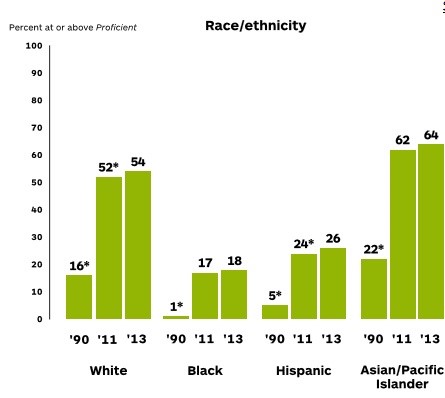

It is not a coincidence that most of the perceived low-achieving students who are pushed out are black students. Black students are more influenced by their teacher’s perception of their abilities than white students and are more likely to be seen as low-achieving [3]. When a black student is pushed out of school for a possibly unnecessary reason and is not allowed to take the state exam, they fall behind academically and are undeservedly labeled as a “bad student.” This is a label that severely damages their self-confidence. This inflicted self-perception is most likely one of the causes of the racial difference in achievement levels reported by the 2013 National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP).

Where do we go from here?

The recommendations included in the Assessment and Accountability for Improving Schools and Learning “reflect the reality that the rigid ‘one-size-fits-all’ approaches to accountability does not work.” Along with many other initiatives, they propose using assessment systems that are appropriate for a diverse student population, as well as replacing the current Adequate Yearly Progress structure with the use of multiple sources of evidence to describe school performance more fairly. Schools should use reports on student progress not so that Washington can decide whether to sanction a school, but so parents, teachers and communities can know whether their students are succeeding. Schools should also be held more accountable for their graduation rate, especially for these at-risk students, rather than putting so much weight on a test score and those in attendance for the exam period.

While school accountability can be valuable in allowing schools to track their students’ progress, schools also need to be responsible for their students of color who are disadvantaged by this push-out trend. The way that schools are funded should change so that schools benefit from keeping students in school. After pushing a low-achieving student out of their school system, the school no longer has to devote resources to that student and is not responsible for their test scores, but it can keep the money that it initially received for that student. The Every Student Every Day Coalition’s Policy Platform suggests that for each day a student misses due to expulsion, the school should be required to pay a penalty equal to the current uniform per-student funding formula, divided by the total number of instructional days in the school’s calendar. This may encourage schools to educate all of their students rather than pushing out those who present a challenge.

Unfortunately, not all schools have the same starting point, making it difficult for all to show the same signs of improvement. All schools are different in the makeup of their student population, the strength of their teachers and the quality and quantity of their resources – which is why each should be able to function differently. Over a decade after the implementation of NCLB, 43 states and the District of Columbia now have received waivers from NCLB that allow them to forgo certain accountability requirements [4]. This overwhelming waiver trend says that NCLB has failed to be realistic and effective on its own. Schools should be given the flexibility to develop accountability measures that work best for them, so that they can ensure the success of all of their students and help them reach their full potential beyond a test score.

[1] Losen, Daniel J. 2005. “The Color of Inadequate School Resources: Challenging Racial Inequalities that Contribute to Low Graduation Rates and High Risk for Incarceration.” Clearinghouse Review Journal of Poverty Law and Policy January-February 2005: 616-632.

[2] Hursh, David. 2007. “Exacerbating Inequality: The Failed Promise of the No Child Left Behind Act.” Race, Ethnicity and Education (10):3, 295-308.

[3] Wald, Johanna and Daniel J. Losen. 2003. Deconstructing the School-to-Prison Pipeline. New Direction for Youth Development, Issue 99. Boston: Jossey-Bass.

[4] Bidwell, Allie. 2014. “Education Department Drops New NCLB Waiver Guidance.” U.S News & World Report, Nov. 13. http://www.usnews.com/news/articles/2014/11/13/education-department-drops-new-no-child-left-behind-waiver-guidance.